Challenging differentiation of oral malignant lymphoma from osteomyelitis of the jawbone: A case report

- Authors:

- Published online on: April 16, 2025 https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2025.2849

- Article Number: 54

-

Copyright: © Munekata et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License.

Abstract

Introduction

Malignant lymphoma (ML) is a neoplasm of lymphocytes, which are a type of white blood cell. Lymphomas are broadly divided into precursor lymphoid tumors, mature B-cell tumors, mature T-cell and natural killer cell tumors, and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) based on the difference in the cell of origin, and neoplasms other than HL are collectively designated as non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the World Health Organization classification revised in 2017(1).

ML is the third most common malignancy in the oral and maxillofacial region after squamous cell carcinoma and salivary gland tumors. However, ML in the oral and maxillofacial region is uncommon, accounting for only 3% of all lymphomas and there is a current lack of reports on oral ML (2).

Most ML cases occurring in the oral and maxillofacial region are NHL. In terms of the site of lesion development, HL is known to occur mainly in lymph nodes, whereas NHL is known to occur extranodally in a large proportion of cases. Furthermore, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common histological type of NHL in the oral and maxillofacial region. These conditions are frequently challenging to diagnose due to their resemblance to inflammatory lesions, such as periodontal disease and osteomyelitis, and other tumors. Therefore, establishing an accurate diagnosis may take some time, thereby increasing the risk of an unfavorable prognosis (2,3).

This report aimed to present a case of ML with a chief complaint of cheek swelling, which was challenging to differentiate from mandibular osteomyelitis. In the present case, it was difficult to distinguish between osteomyelitis of the jawbone and ML because the patient did not show any of the B symptoms that are specific to patients with ML, and there were no clear abnormalities in the blood test results for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) or soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R). In addition, it was difficult to identify the site of the lesion, so it was not possible to perform a biopsy from an appropriate site.

Case report

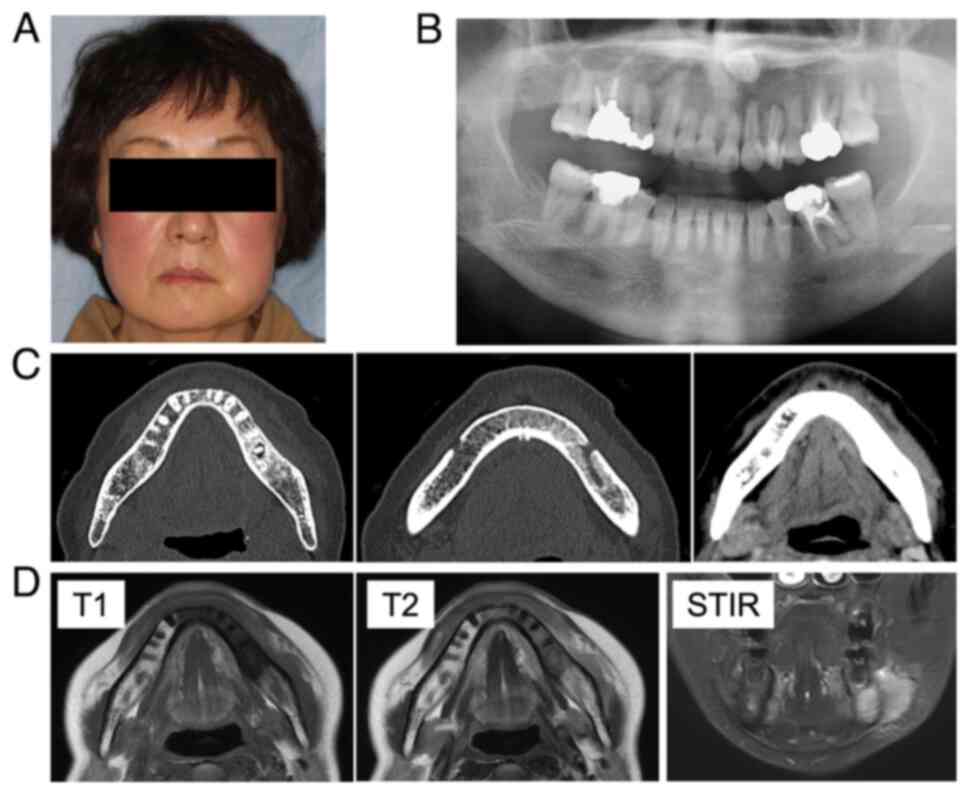

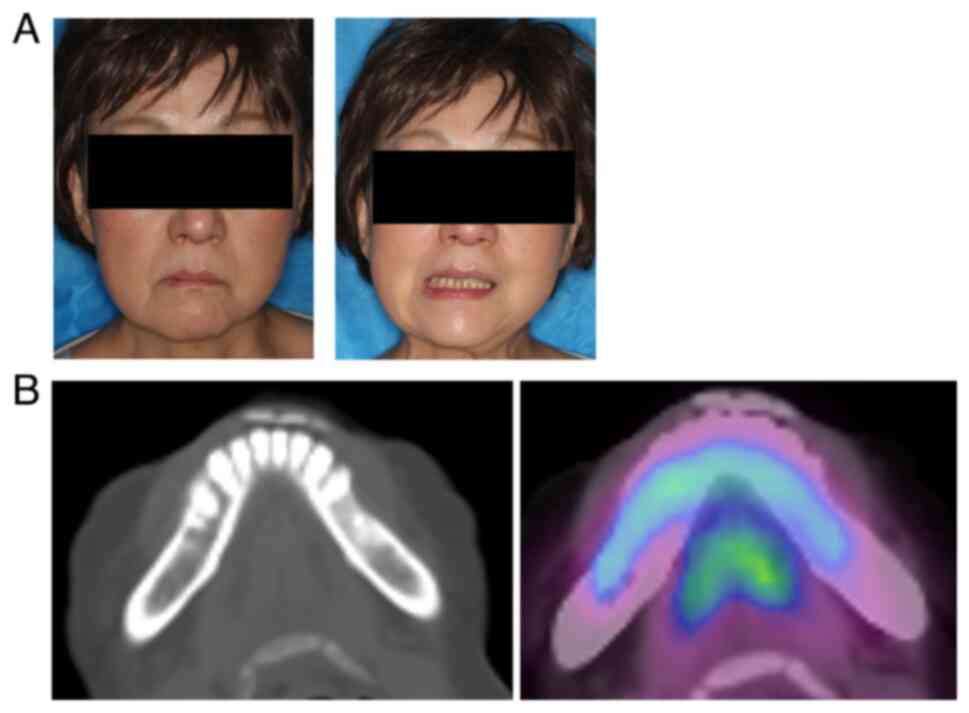

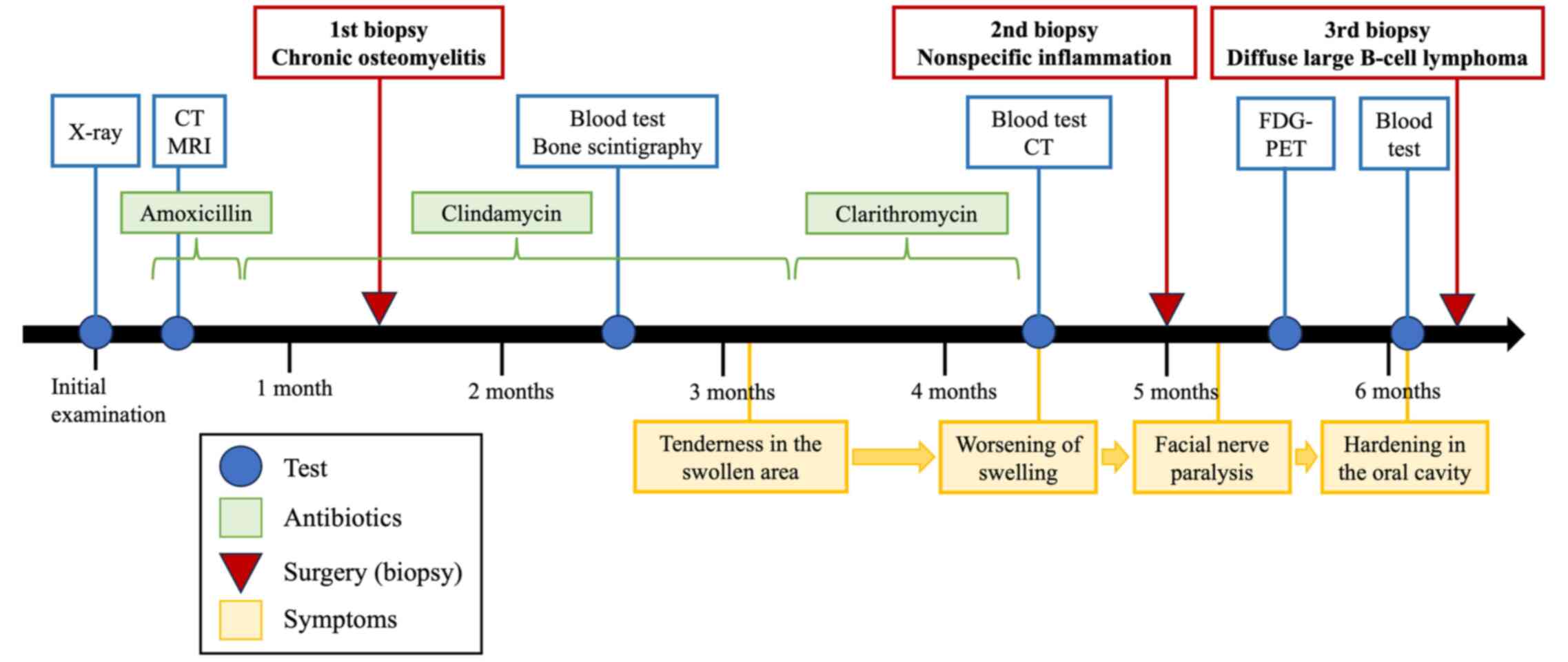

A 59-year-old woman noticed painless swelling on the left side of her face and sought consultation at the Department of Oral Surgery, Sapporo Teishinkai Hospital (Sapporo, Japan) in September 2021. An imaging test performed at the same institution showed osteomyelitis of the left mandible and cellulitis of the left cheek. The patient was referred to Department of Oral Medicine, Hokkaido University Hospital (Sapporo, Japan) for further examination. Her family history revealed no notable abnormalities. Her medical history included dyslipidemia. The general physical examination revealed an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0. She had no recent history of sudden weight loss, fever, or night sweating. The extraoral examination revealed diffuse swelling of the left lower jaw and cheek. However, no evidence of redness or tenderness in the same area was observed (Fig. 1A). Additionally, no evidence of inferior alveolar nerve paralysis, facial nerve paralysis, or trismus was observed. Although swelling and slight tenderness were observed in the oral vestibule of the left mandibular molar region, no evidence of tooth mobility or percussion pain was observed in the left mandibular molar teeth. The initial X-ray examination revealed a radiolucent image at the apex of the distal root of the left mandibular first molar and sclerosis of the surrounding bone (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, contrast-enhanced CT revealed a radiolucent image at the apex of the distal root of the left mandibular first molar and extensive bone sclerosis extending from the left mandibular anterior teeth to the left mandibular ramus. Additionally, mild swelling was observed in the soft tissue surrounding the left mandible (Fig. 1C). The MRI examination revealed a low signal on T1 and a slightly high signal on T2 in the region extending from the left mandibular incisor to the body of the bone, and soft tissue swelling was observed along the buccal mandible in the same area (Fig. 1D). Based on these findings, osteomyelitis of the left mandible and apical periodontitis of the left mandibular first molar were suspected as the cause of the buccal swelling. Consequently, a decision was made to extract the left mandibular first molar, which was considered the causative tooth, following anti-inflammatory treatment with antibiotics.

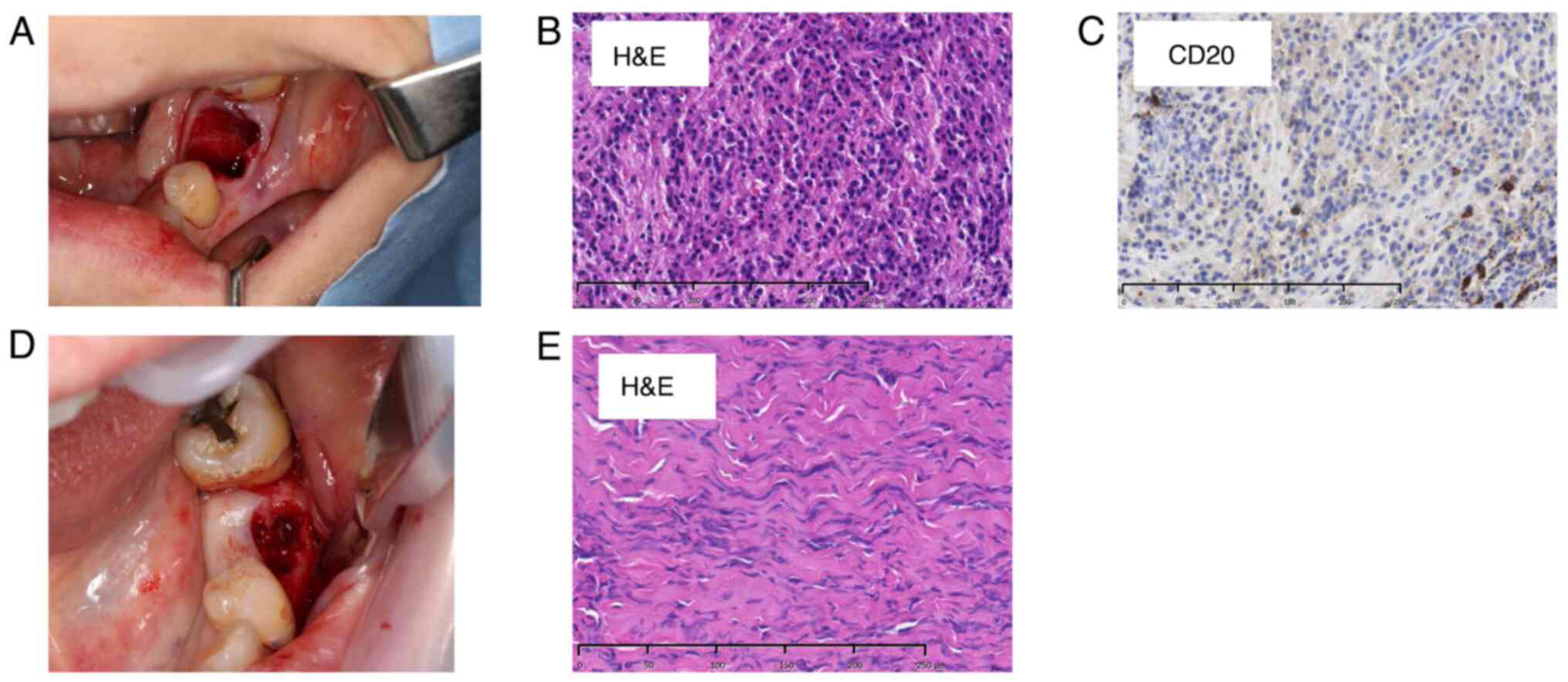

Amoxicillin was initially administered to reduce inflammation. However, the patient experienced a rash, and amoxicillin was changed to clindamycin. However, the cheek swelling did not improve. Moreover, although the left mandibular first molar was identified as the causative tooth, a considerable extent of the sclerotic bone was observed. After extraction, bone and surrounding soft tissue samples were obtained from the same site and underwent comprehensive pathological examination (Fig. 2A). The initial biopsy results revealed mild lymphocyte infiltration in the medullary cavity of the hard tissue and moderately infiltrated granulation and fibrous tissue with inflammation, mainly composed of lymphocytes, in the soft tissue. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with chronic osteomyelitis (Fig. 2B).

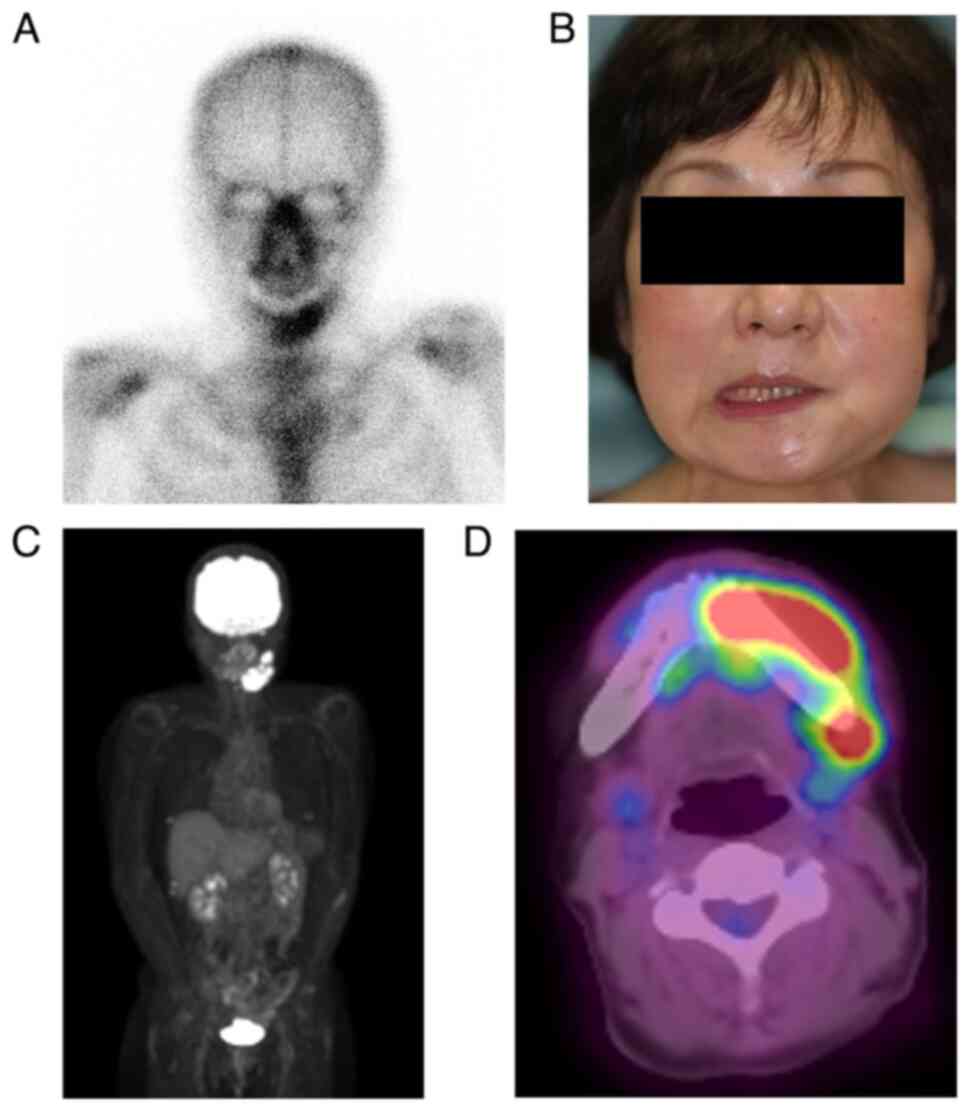

After the initial biopsy, clindamycin was continued to reduce inflammation. However, no improvement in cheek swelling was observed. The possibility of a malignant tumor, including ML, or diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis of the mandible was considered. Additional blood tests and bone scintigraphy were performed. The blood test results showed that the white blood cell count and C-reactive protein level were within the normal range, and no evidence of an inflammatory response was observed. Furthermore, no abnormalities in LDH, which is specific to ML and considered effective for diagnosis, was observed (Table I). Conversely, bone scintigraphy revealed increased radiopharmaceutical activity accumulation in the left mandible region, indicating mandibular osteomyelitis (Fig. 3A).

The biopsy site was epithelialized and exhibited healing signs 3 months after the initial examination. However, the cheek swelling and tenderness at the same site worsened. Therefore, the antimicrobial agent was changed to clarithromycin. Additional blood tests and contrast-enhanced CT scan were performed. However, the blood test showed only a slight increase in LDH, which is thought to be due to liver dysfunction, and sIL-2R was also within the normal range, so there were no notable abnormalities, and the cause remained unknown (Table I). Therefore, a biopsy was performed at the initial site, and the bone and buccal periosteum samples were obtained (Fig. 2D). The pathological results of the second biopsy revealed inflammatory cell infiltration in the bone and soft tissue. However, no malignant findings were observed (Fig. 2E). After that, no additional antimicrobial agents were administered.

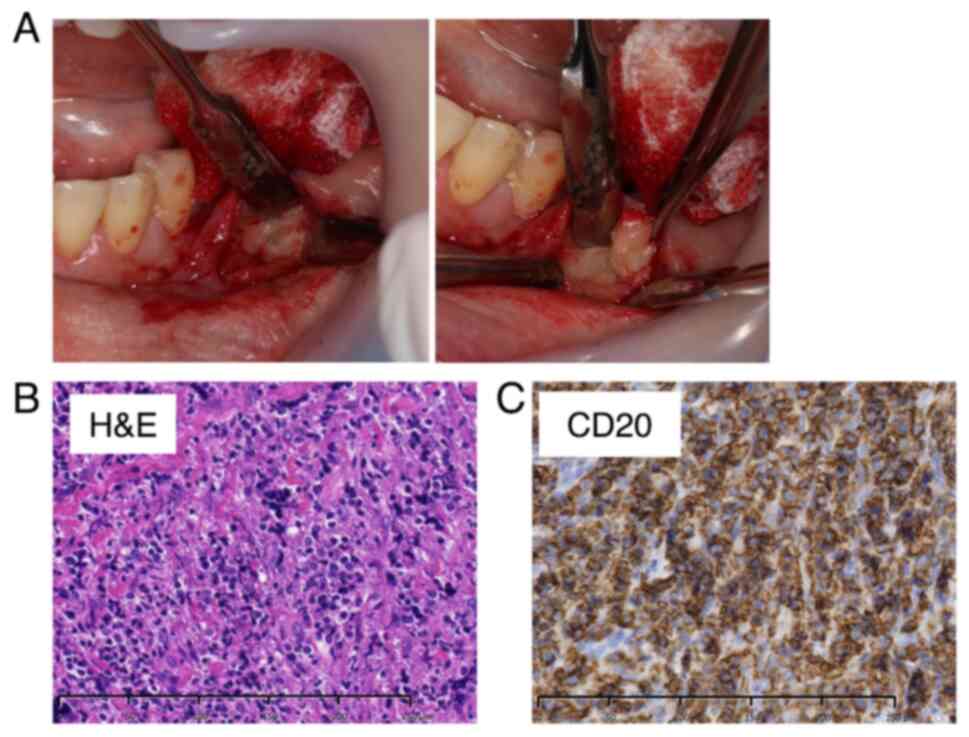

The patient developed facial paralysis of the left mandibular branch 5 months after the initial examination, which had not occurred previously (Fig. 3B). Therefore, FDG-PET was performed to rule out the possibility of a malignant tumor. The examination results showed no abnormal accumulation throughout the body (Fig. 3C). However, a notable increase in accumulation was observed in the region extending from the body of the left mandible to the area surrounding the mandibular ramus, indicating mandibular osteomyelitis (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the blood test results revealed no abnormalities in the inflammatory response, LDH, or sIL-2R (Table I). An unexpected swelling with hardening was then observed in the left mandibular fossa. Therefore, a third biopsy was performed. A sample of the milky white soft tissue was obtained from the hardening site (Fig. 4A). The pathological results confirmed ML through hematoxylin and eosin staining. Additionally, the diagnosis of DLBCL was made due to the atypical B-cell proliferation observed in various immunostaining tests (CD20+, CD3-, CD56-, and EBER-) (Fig. 4B and C). Furthermore, according to the Hans classification, a classification of DLBCL based on gene activity patterns, a germinal center B-cell-like type was identified, exhibiting CD10-, Bcl-6+, and MUM- expression. According to the Ann Arbor staging system for ML, the patient was classified as being in Stage I. After confirmation of the diagnosis of ML, immunostaining was performed using the sample obtained from the initial biopsy. However, only minor CD20- and CD3-positive cells were observed in the lymphocytes, and no evidence of ML was identified (Fig. 2C).

R-CHOP therapy (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) was initiated and administered in six courses. After the sixth course of treatment, the examination revealed resolution of the swelling of the left cheek and soft tissue in the mouth and improvement of the facial nerve paralysis. FDG-PET showed no evidence of intense accumulation in the body of the mandible. The patient is currently under observation without recurrence (Fig. 5A and B). Fig. 6 shows the symptoms and treatment process leading to remission.

Discussion

NHL is the most prevalent blood cancer worldwide. It is the seventh most frequently diagnosed and sixth most lethal type of malignant tumor in the United States. Histologically, NHL exhibits a proliferation of B and T cells, and it is distinguished from HL by the absence of Reed–Sternberg cells and CD15 and CD30 staining. Additionally, the clinical features of NHL and HL are notably different (4). The etiology of this disease remains unclear, and the primary risk factors include autoimmune diseases, infections, exposure to harmful chemicals, and radiation exposure (5,6).

DLBCL is the most prevalent form of NHL, accounting for 30-40% of adult cases. It manifests in two distinct patterns: nodal (within a lymph node) and extranodal (outside a lymph node) (4). DLBCL can manifest in nearly any organ. However, initial manifestations in the oral and maxillofacial region are uncommon. Nevertheless, the prognosis of patients with DLBCL that develops in the oral cavity or oropharynx is poor, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis for optimal treatment outcomes (7). In the diagnosis of DLBCL, the presence of systemic symptoms, known as B symptoms, is indicative of the disease. These symptoms include fever (unexplained fever of ≥38˚C), night profuse sweating, and weight loss (unexplained weight loss of >10% within 6 months before diagnosis). Additionally, serum LDH and sIL-2R are considered biomarkers (8,9). Although these factors are useful in prognostication, they only aid in diagnosis. There are DLBCL cases, such as our case, that do not present with systemic symptoms or abnormalities in blood tests. Furthermore, if ML is not initially considered a differential diagnosis, opportunities to measure it in blood tests will be limited.

The oral and extraoral symptoms of DLBCL occurring in the oral and maxillofacial region include a wide range of manifestations, such as painless swelling, tooth mobility, ulceration, and jaw and cheek numbness (7,10). In cases where the disease manifests within the mandible, patients may experience a loss of sensation in the region of the inferior alveolar nerve, which is clinically referred to as numb chin syndrome (11). Nevertheless, previous reports have shown that a considerable proportion of patients with DLBCL remain asymptomatic during the initial stages of the disease. The diverse range of symptoms that emerge as the lesion progresses may be due to the high incidence of clinical misdiagnosis and delays in making a definitive diagnosis (12). Table II shows case reports of DLBCL in the oral cavity published in the last 10 years on PubMed (13-27). The majority of cases were males aged ≥40 years. The onset sites were considerably variable, including the gums, jawbone, and mucous membranes. Additionally, the symptoms were considerably diverse, including swelling and ulcer formation. Moreover, in most of these reports, patients did not present with B symptoms. These findings indicate that biopsy is crucial for accurately diagnosing DLBCL in the oral cavity. Furthermore, the onset of DLBCL has been suggested to be associated with autoimmune diseases and the use of immunosuppressants (16,19). Additionally, the presence or absence of Epstein-Barr virus infection (13,19) can be used as a diagnostic aid.

As in our case, some DLBCL cases presenting with cheek swelling as the primary complaint have been reported. However, many of these cases have been found to involve bone destruction on X-ray images, with the primary lesion situated in the jawbone or gums (3,7). Nevertheless, reports of cases in which the primary lesion is located in the soft tissue surrounding the jawbone are limited. In our case, radiography revealed a radiolucent image at the apex of the distal root of the left mandibular first molar, and sclerotic bone was observed around it. Based on these findings, a dental infection caused by the left mandibular first molar was suspected to be the causative tooth. However, extensive bone sclerosis from the anterior teeth to the mandibular ramus was observed on contrast-enhanced CT images, indicating the possibility of other diseases, including tumors, that could not be ruled out. However, since the primary lesion was strongly suggested to be within the jawbone or periosteum, a biopsy on the buccal soft tissue near the mandible was not performed at the time of the initial examination. Furthermore, X-ray images obtained after R-CHOP therapy showed no bone destruction in the mandible, with the jawbone maintaining its original shape. This finding indicated that the primary lesion was not within the jawbone, periosteum, or gingiva, but rather in the surrounding soft tissue.

In this case, although the images showed changes in the bone marrow, the main lesion was in the soft tissue around the jawbone. Therefore, the specimens could not be obtained from the main lesion in the two biopsies. Furthermore, the lesions were extranodal and localized to the buccal soft tissue. Therefore, the typical blood test findings and B symptoms of ML were not observed, making the identification of the underlying disease difficult.

However, cases of osteomyelitis of the jaw in which antibiotics are ineffective and in which no inflammatory response is detected in blood tests, as in this case, are extremely rare. In answering this question, it is necessary to always bear in mind the possibility that other diseases may be lurking in the background, but in particular, it is necessary to be careful about the clinical stealthiness of oral DLBCL, which shows symptoms similar to dental diseases. Therefore, when making a differential diagnosis, it is important to actively perform a wide range of tests, including not only imaging tests but also blood tests such as LDH and sIL-2R, and FDG-PET. In addition, in order to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis, it is desirable to perform a biopsy as early as possible, and this will also improve the patient's prognosis.

In conclusion, in cases of intractable cheek swelling and atypical osteomyelitis, a treatment plan that includes ML as a differential diagnosis is essential. A pathological diagnosis by biopsy is crucial for accurate diagnosis. Additionally, because many cases of ML in the mouth present with atypical symptoms, determining the location of the main lesion at the time of biopsy is essential.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TM collected the clinical data and wrote the manuscript. TM, TA, KS, TK, CIS and YK acquired and interpreted the clinical data. AM and NM performed the pathological examination. TA, KS, and TK revised the manuscript. CIS and YK confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for the publication of the clinical data, including photos and images, was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

|

de Leval L and Jaffe ES: Lymphoma classification. Cancer J. 26:176–185. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Silva TDB, Ferreira CBT, Leite GB, de Menezes Pontes JR and Antunes HS: Oral manifestations of lymphoma: A systematic review. Ecancermedicalscience. 10(665)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Bugshan A, Kassolis J and Basile J: Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the mandible: Case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol. 8:451–455. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Thandra KC, Barsouk A, Saginala K, Padala SA, Barsouk A and Rawla P: Epidemiology of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Med Sci (Basel). 9(5)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Zhang Y, Dai Y, Zheng T and Ma S: Risk factors of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 5:539–550. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Rodrigues-Fernandes CI, Junior AG, Soares CD, de Lima Morais TM, do Amaral-Silva GK, de Carvalho MGF, de Souza LL, Pires FR, Dos Santos TCRB, Pereira DL, et al: Oral and oropharyngeal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and high-grade B-cell lymphoma: A clinicopathologic and prognostic study of 69 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 131:452–462.e4. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Michi Y, Harada H, Oikawa Y, Okuyama K, Kugimoto T, Kuroshima T, Hirai H, Mochizuki Y, Shimamoto H, Tomioka H, et al: Clinical manifestations of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that exhibits initial symptoms in the maxilla and mandible: A single-center retrospective study. BMC Oral Health. 22(20)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Yoshida N, Oda M, Kuroda Y, Katayama Y, Okikawa Y, Masunari T, Fujiwara M, Nishisaka T, Sasaki N, Sadahira Y, et al: Clinical significance of sIL-2R levels in B-cell lymphomas. PLoS One. 8(e78730)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Qi J, Gu C, Wang W, Xiang M, Chen X and Fu J: Elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels display a poor prognostic factor for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in intensive care unit: An analysis of the MIMIC-III database combined with external validation. Front Oncol. 11(753712)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Armitage JO, Gascoyne RD, Lunning MA and Cavalli F: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 390:298–310. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Jain A, Rajpal S, Sachdeva MUS and Malhotra P: Numb chin syndrome as a presenting symptom of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with secondary myelofibrosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018(bcr2017221245)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Storck K, Brandstetter M, Keller U and Knopf A: Clinical presentation and characteristics of lymphoma in the head and neck region. Head Face Med. 15(1)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Hong YR, Kwon JS, Ahn HJ, Han SY, Cho E and Kim BE: Importance of differential diagnosis of EBV mucocutaneous ulcer and EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 103(e37243)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Abeles EB, Umrau K, Gray ML and Boahene KD: Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the nasal bone and palate: An unusual clinical presentation. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 26:572–575. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Gante J, Georg S, Robez JMG, Dubuc A and Lauwers F: Primary extra-nodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma affecting mandibular bone: A case report. Pan Afr Med J. 41(231)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Vardas E, Georgaki M, Papadopoulou E, Delli K, Kouroumalis A, Kalfarentzos E, Lakiotaki E and Nikitakis NG: Diagnostic challenges in a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the maxilla presenting as exposed necrotic bone. J Clin Exp Dent. 14:e303–e309. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Liu K, Gao Y, Han J, Han X, Shi Y, Liu C and Li J: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the mandible diagnosed by metagenomic sequencing: A case report. Front Med (Lausanne). 8(752523)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Shilkofski JA, Khan OA and Salib NK: Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the anterior maxilla mimicking a chronic apical abscess. J Endod. 46:1330–1336. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Obata K, Okui T, Kishimoto K, Ibaragi S and Sasaki A: Methotrexate-associated lymphoproliferative disorder developed ectopically in the maxillary gingiva and bilateral lungs. Case Rep Med. 2020(4814519)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Puneeth HK, Kumar SRR, Ananthaneni A and Jakkula AN: Physical torment: A predisposition for diffuse B-cell lymphoma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 23 (Suppl 1):S17–S22. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Narang RS, Manchanda AS and Kaur H: Evaluation of a case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 23 (Suppl 1):S7–S11. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Fuessinger MA, Voss P, Metzger MC, Zegpi C and Semper-Hogg W: Numb chin as signal for malignancy-primary intraosseous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the mandible. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 8:143–146. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Zou H, Yang H, Zou Y, Lei L and Song L: Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the maxilla: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 97(e10707)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

de Castro MS, Ribeiro CM, de Carli ML, Pereira AAC, Sperandio FF, de Almeida OP and Hanemann JAC: Fatal primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the maxillary sinus initially treated as an infectious disease in an elderly patient: A clinicopathologic report. Gerodontology. 35:59–62. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Vrbic M, Petkovic I, Vrbic S, Jovanovic M, Rankovic A, Popovic-Dragonjic L and Djordjevic-Spasic M: Two-year complete remission of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an immunological nonresponder HIV-infected patient: Case report. Case Rep Oncol. 10:356–360. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Patil AV, Deshpande RB, Kandalgaonkar SM and Gabhane MH: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (extranodal) of maxillary buccal vestibule. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 19(270)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar | |

|

Sahoo SR, Misra SR, Mishra L and Mishra S: Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the anterior hard palate: A rare case report with review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 18:102–106. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar |